This blog post has been written by special invitation of The Courtauld.

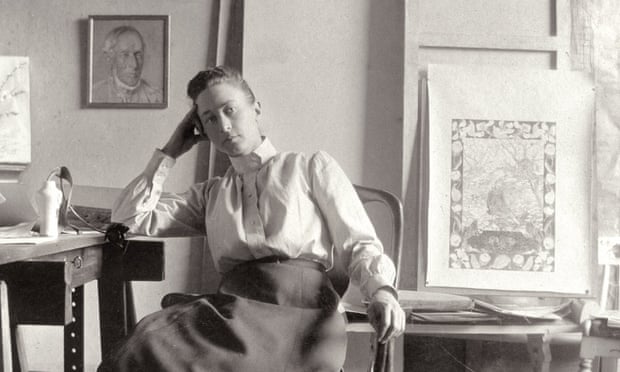

Georgiana Houghton is, no doubt, an unfamiliar name to most gallery visitors; a name more likely known to experts in Victorian Spiritualism. Houghtom’s work is remarkable: it is organic, oceanic, ephemeral, religious, spiritual and anachronistic. Houghton has been described as an eccentric and worse, as an amateur, and this summer presents us with a chance to decide for ourselves.

Born in 1814 in Las Palmas, in Gran Canaria, Houghton later made London her home. It was in London, at the New British Gallery in Bond Street, that she made a brave and yet ultimately unfortunate decision; in 1871, Houghton decided to exhibit one hundred and fifty five of her spiritualist drawings at her own expense, using an inheritance of £300 (about £30,000 today). She nearly bankrupted herself in the process. The works on display at The Courtauld this summer have not been exhibited in Britain since that time, not since the nineteenth century.

The ‘Georgiana Houghton: Spirit Drawings’ exhibition, at a cost of £9 to the average visitor, has been a resounding success. The press have discussed it quite intently, and floridly too, awarding it five stars and using words like ‘awe-inspiring (The Guardian) and claiming The Courtauld is ‘rewriting art history’ (Sunday Times). Likewise, Twitter has appeared kind and engaged with Houghton’s works, surprised by them even. During my own visit I went from being extremely disappointed that not more people were there enjoying the exhibition to smiling that quite a crowd had arrived by the time I left.

The Courtauld’s objectives are clear, and the curators (Simon Grant, Lars Bang Larsen and Marco Pasi) are intent on positioning Houghton as ‘a fascinating precursor of twentieth century abstract art’. I am sure she is and should and can be discussed in these terms, but isn’t that rather typical and perhaps even rather lazy thinking and criticism? What is this desire to position Victorian art as firmly related to Modernism? Why is it only acceptable to us in the twenty-first century, if we can see Victorian Art (and literature too) as belonging to us somehow? Why does the nineteenth century need to be related to our own for us to accept what came out of it, or to even bother to stop and look at objects from that time?

A cynic may say this is canny marketing and perhaps it is, although I think the PR desire to make history appeal and be accessible to us all, is driven by our desire for the Victorians to be like us, or at least seem to be like us. We desire to consume them, but in doing so have to first make them familiar and consumable.

If we view Houghton’s works through the lens of say someone like Georgia O’Keeffe (cue the big expo on at the Tate this autumn) she feels a little more like us, and a little less like, well, herself, or rather less like the Victorian spiritualist she was. But such an approach does Houghton an injustice doesn’t it? She certainly wasn’t like us in any way, and approaching her work as purely a precursor to abstract art misses and indeed negates the very heart of what drove Houghton’s work. It is hard to imagine a woman so belligerently dedicated to her work that she nearly bankrupted herself would relish our engagement with her work as being largely a form of early abstract art (however flattering we see that accomplishment as being). How would Houghton feel at our lack of engagement with (read blatant overlooking or at our most polite, a mere diminishing of) the hand of Titian, St. Luke, or the Lord Christ himself, for these were the people Houghton claimed she channelled through the production of her art.

The Courtauld ‘Summer Showcase’ brief mentions Barnaby Wright’s view that Kandinsky and his predecessor, Hilma af Klint are part of Houghton’s lineage (Wright being The Courtauld’s Twentieth Century curator). “I think Houghton does count as being among the first abstract artists,” said Wright. “She is obviously earlier than Klint. If one is playing that race then she steals a march.”

Of course, these hints to the modern day audience are essential to pitch a corpus of work which has been hidden from British eyes in the last hundred and fifty years, and one should not deny their accuracy. One can hardly blame The Courtauld for such posturing; it is this very repositioning of Houghton which the Sunday Times refers to as the ‘rewriting of art history’ and remains the dictate of The Courtauld’s ongoing and commendable Summer Showcase programme.

Some fifty paintings of Houghton’s are known to exist: thirty five of which have been in the care of the Victorian Spiritualist Union (VSU) of Melbourne, Australia since 1910, with an album of eight further works held by the College of Psychic Studies in London (this album is included in the exhibition). It is not known how many works she produced but in the 1871 exhibition, Houghton exhibited 155 works so there may well be many more out there in private collections or languishing in dusty draws somewhere. There are twenty one on display at The Courtauld.

Unlike the 2016 show, the 1871 exhibit was met with confusion by perplexed critics. The Era pronounced it to be ‘The most astonishing exhibition in London at the present moment’. The Daily News likened the works to ‘tangled threads of coloured wool’…that deserved ‘to be seen as the most extraordinary and instructive example of artistic aberration’. One critic wrote how ‘a visitor to the exhibition is alternatively occupied by sad and ludicrous images during the whole of his stay in this gallery of painful absurdities’, while another wrote of ‘the strange hallucinations of which the human mind may be capable… If we were to sum up the characteristics of the exhibition in a single phrase, we should pronounce it symbolism gone mad.’

During the three month exhibition, which The Courtauld mirrors in time frame, Houghton would spend time discussing her works with visitors. Her attention to detail was important to her, down even to the date she produced each drawing and to their display: she hammered ‘in every nail with my own hands’ and had boys walk the streets with placards to advertise the show. She placed notices in specialist newspapers and printed a special catalogue for Queen Victoria, in pink satin and white calf, as well as the standard version in pink tinted paper and a brown cloth cover, a copy of which is in The Courtauld show.

‘Guiding’ was seemingly an intrinsic part of Houghton’s art practice, for both justification and production. Houghton described her brightly coloured watercolours as having been produced by the ‘guiding’ hand of spirit friends. These were no run of the mill spirits though, for they ranged from Titian to Correggio and the aforementioned St. Luke (the artist’s saint of choice) and Christ. But do not let that sway you, for Houghton was a serious woman, who sought to be taken seriously.

Houghton was formally trained as an artist, likely in France, and recorded herself as an artist in census records. She submitted works to the RA and to the Dudley Museum and Art Gallery, but her work was presumably too anachronistic for the palate of the day. At this time, viewers had only just adjusted to the likes of the Pre-Raphaelites, and were still in the process of accepting J.A.M Whistler and Claude Monet.

Houghton’s works were not about telling narratives, she intended them to ‘show what the Lord hath done for my soul’. Christianity was life affirming and art inspiring for Houghton, who embraced spiritualism after the loss of younger sister, Zilla, herself an artist (Houghton lost four of her nine siblings in total).

It was as a forty-five year old spinster that Houghton attended her first séance, in 1859, at the home of the medium Mrs Marshall, who was described in the press as ‘a short, fat woman with small eyes’. The séance reportedly went well, with Houghton hearing a sequence of knocks, as well as communication from Zilla on a subject about which no one else in the room could have known. It left her ‘filled with astonishment’ and set her on a journey, one encouraged by her mother, to become a medium.

Houghton began with table-tipping, where participants hold the table and wait for it to jerk suddenly, much like the séances Dante Gabriel Rossetti, J.A.M Whistler, and William Holman Hunt had also attended. Houghton then progressed to the planchette, which is a heart-shaped piece of wood, mounted on two wheels and with a hole for a pen, designed specifically for written contact with the spirits.

Spiritualism actually began with the Fox Sisters in New York in 1848, and although an American born movement, it arrived in Britain in 1852. Its primary claim was that the living could make contact with the dead, or vice versa. Many American mediums came across the Atlantic to set up shop in Britain and made their money by causing a stir and in some cases taking advantage of the bereaved (one could argue that in the case of Rossetti). Both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert had participated in séances and been visited by psychics and mediums whilst he was still alive, and, George VI is said to have found a detailed record of a John Brown led séance in which Victoria attempted to contact Prince Albert, many years later (this was mentioned to his speech therapist, Lionel Logue).

Spirit photographs, séances and excitable table-tipping stories all created a stir in London, and Houghton was part of the scene, for better or worse. After the financial damage caused by her exhibition, Houghton became associated with the fraudulent spirit photographer Frederick Hudson and sold reproductions of his photographs. In 1882, Houghton published Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings and Phenomena Invisible to the Material Eye which included spirit and medium photographs from Hudson and others, although the images were criticised and considered easily rendered by fraudulent methods. Disregarding the well documented fraudsters, Houghton’s motives seem to have been honest (at least until her post-exhibition financial crisis) and she wrote in her autobiography that she believed her work with Hudson had been genuine (she appears in the background of two hundred and fifty odd photographic works of his).

Houghton’s motives seem to have been intrinsically bound up within her own sincere Christianity. Her pursuit of spirit drawings came about after learning that one medium, Mrs. Wilkinson, produced drawings whilst in a trance. A mere two years after attending her first séance, Houghton, in 1861, produced the first of probably several hundred drawings which she described as being ‘without parallel in the world’. One only has to look at the works at The Courtauld, specifically the verso where possible, to get a feeling of Houghton’s sincerity. In The Spectator, Simon Grant writes that ‘her Christian faith sustained her belief, not just in herself, but in her art’.

Houghton’s titles are often religious in form, e.g. The Eye of God (also The Eye of the Lord) (22nd September, 1866?, year partially obscured, VSU), The Sheltering Wing of the Most High (2nd October,1862, VSU) or Houghton, The Portrait of the Lord Jesus Christ (8th December, 1862, VSU) (the only figurative work in the display). The Eye of God (1st September, 1870, VSU) is a particularly interesting work which succinctly conveys Houghton’s belief, and art practice. On verso, seven archangels are listed as having contributed to the production of this pen and ink work. An inscription on the lower left identifies them as the ‘8th’ of Houghton’s believed hierarchy of ten angels (typically angels are ranked in three sets of three – from Cherubim to Angels).

Houghton considered her drawings a form of religious art and works like The Risen Lord (29th June, 1864) were specifically centred around the sufferings of Christ’s time here on earth (guided art pieces as they were). Despite the innate religiosity of the drawings, The Glory of the Lord (4th January, 1864, VSU) was described during the 1871 exhibition, as being reminiscent of Turner, a man whose relationship was at best rooted in a natural rather than spiritual theology. The News of the World described the work ‘as a canvas of Turner’s, over which troops of fairies have been meandering, dropping jewels as they went’. This beautiful description does justice to Houghton’s colours and forms but not to her religiosity. There were no fairies trooping, only angels and saints. It is comforting that The Courtauld displays the verso of some works, so that viewers can at least confront this intrinsically Christian aspect. How does one resolve her list of angels though?

The angel names provided are obscure, and do not generally correspond to scripture: Misrael is presumably from the derivative of Michael, meaning ‘who is like God?’ but the other names and origins are not obvious. It is telling that these details were a deliberate means of Houghton authenticating her art production and practice. Angels traditionally inhabit the role of the ‘unveiler’, the messenger, so by choosing angels as her spirit guides Houghton immediately distances herself from her output and places it in the hands of the celestial spirit world. It is the message of the angels which Houghton conducts. Her annotations and the arrangement of her images with her automatic script are very much part of the sincerity of the works. It is also interesting to note, that despite The Courtauld attempting to focus visitors attention on modernist styles and forms, they presumably deliberately create a space where one must approach the ones in such a manner that one recalls the altar.

Scripture by virtue of its medium is narrative, but one curious complexity of Houghton’s spirit drawings is their refusal to be narrative. They do not recall scripture in the same manner as didactic Ruskinian lectures, instead they summon light and dark and bodily and spiritual emotions. Houghton’s paintings are a quest which moves beyond the figurative, the allegorical or the narrative of much Victorian art, and in doing so demands and expects much more from its viewers.

The tangled mess of the works is often jellyfish like, spongey, ethereal and liable to change with every look one casts in their direction. The forms morph and twist before your eyes and although at first you may see nothing but swirls and colours, you soon start to disappear into your own deeply personal, nay spiritual, reverie and harmony. The works are emotional because they communicate not with the dead, but beyond life and people: they are otherworldly, they are drawn from the angels, they are celestial. These paintings are not for the common mind, they are for the mind that is open, that is able to abstract and to think beyond this earthly sphere. Houghton’s art practice was clearly ‘different’ (who are we to judge it to have been ‘eccentric’?) from the typical art school type, but then, it wasn’t merely about art was it, it was about theology, religion, spiritualism, life, and death. The other name of death is, as Ruskin wrote, ‘separation’ and Houghton sought to close that gap of separation between this world and the next by opening new channels of thinking and communicating.

As well as producing monograms, there are also works which were described by Houghton as being ‘spirit flowers’. Her sister Zilla has a fine example in Flower of Zilla Warren (31st August, 1861, VSU) – note the date in relation to Houghton’s taking up of spiritualism, and the daughter of Queen Victoria as represented in The Flower of Victoria Princess Royal of England (22nd April, 1864, VSU). It is easy to become sceptical of such Royal flattery, but regardless of such modern twenty-first century cynicism, as far as I am aware Houghton always maintained she was merely the channel for the drawings rather than responsible as designer. God was the designer, the spirits were merely her friends in rendering and making visible God’s message, and we all had a spirit flower from the time we were born. There is at least consistency in Houghton’s thinking and output. One visitor remarked upon Houghton’s capacity to maintain conversation whilst being engaged in drawing, but this was merely additional evidence for her role as conduit, as channel. Houghton was the Lord’s vessel.

If one was to describe the forms within her paintings one may flounder, and indeed many of the reviews seem to steer clear of really engaging with the look and feel of Houghton’s Spirit Drawings. Simon Grant offers one means of explaining the bafflement of critics: ‘nobody had a language to explain these odd-seeming images’. It is quite feasible that our language has become even less suitable for engaging with such spiritualist works, despite The Courtauld’s attempts at recapitulating them into the twentieth / twenty-first century in order that we may easily grasp their meaning. But these images are of their time, they are Victorian. Our world has become so secular, so rational, that the religious poetry of Houghton is not easily accessible to us. We have to stand and look at the peacock swirls, and bright sunlight daubs, the trailing forms of life and love, the energy within and without the paintings. We have to look and feel the close up intimacy of Houghton and her angels if we are to receive any of her artistic, let alone Christian energy. Can one walk away without engaging with the Christian spiritualist message of her works? Why, yes, of course. But that is not what Houghton would have wanted.

It seems the most honourable and honest way to encounter these works is to at least acknowledge and receive the angels and saints and past masters whom Houghton clearly loved and admired, and sought artistic and personal spiritual guidance from. If we discount (at least whilst in the exhibition) Kandinsky, Klint, Mondrian and any other abstract artist you care to bring into the conversation, we have a hope of becoming a receiving conduit and vessel for Houghton’s highly emotional and spiritual works. I don’t think it matters if we aren’t all experts in Victorian spiritualism, but we do at least need to acknowledge the context these works spring from. Kandinsky can wait. O’Keeffe though? Now, I definitely think there is mileage in comparative analysis there…Perhaps Houghton was a nineteenth century O’Keeffe, full of flowers and light? Have a look at The Flower of Warrand Houghton (18th September, 1861) and see.

Both O’Keeffe and Houghton clearly developed abstract languages of art born from organic forms in order to transcend the everyday realm of consciousness. Houghton used spiritualism, O’Keeffe the desert. Houghton’s automatic writing and trance like drawings are mesmerising and deserve more attention. Forget the big exhibition at the Tate for a moment and invest in some quality energising works by an artist whose reputation will continue to bloom after this sensitively arranged display.

You can access Houghton’s book, Chronicles of the photographs of spiritual beings and phenomena invisible to the material eye (London: E.W. Allen, 1882), here.

You can access Houghton’s autobiography, Evenings at home in spiritual séance (London: E.W. Allen, 1882), here.

Leave a comment