This review has been written by special invitation of The Guildhall Art Gallery

The Guildhall’s current exhibition is a collaboration with the Courtauld Institute and King’s College London. The motivations behind the exhibition are rooted in a celebration of telegraphy, which began one hundred and fifty years ago. The Press had a sneak preview on the 16th September before the official opening on the 20th September. The exhibition, which is free to enter, will be in situ until the 22nd January.

Telegraphy, which essentially means to write at a distance, is the long-distance transmission of textual or symbolic (as opposed to verbal or audio) messages without the physical exchange of an object bearing the message: no carrier pigeons here.

A ‘telegraph’ is a device for transmitting and receiving such messages over long distances, and generally refers to an electrical telegraph. Telegraphy relies upon any chosen message encoding is known and understood by both sender and receiver. Pavel Schilling invented one of the earliest electrical telegraphs in 1832, although Samuel Morse (of Morse code fame) independently invented and patented the electrical telegraph in the United States in 1837.

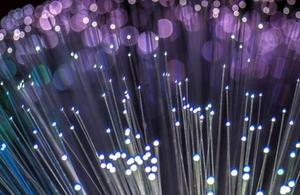

Major innovations such as the successful laying of cable along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean meant that exchanges which would typically have taken weeks by ship, were possible within a single day. These innovations were down to the understanding and resultant harnessing of electricity, and consequentially they forever altered the way people lived and communicated. These advances were the beginnings of the world we now inhabit, where email and the internet is always at hand and fast becoming an individual’s ‘right’ to have. Recent Government policy has been designed to provide ‘superfast broadband (speeds of 24Mbps or more) for at least 95% of UK premises and universal access to basic broadband (speeds of at least 2Mbps)’ by 2017.

Our view that today’s technologies are both essential and our ‘right’ relates back to the nineteenth century’s revolutionary changes in the communication landscape and their creating a world that was ‘connected’ – a word we overuse today. Victorian innovations have now become accepted as a standard way of life, and the ‘Victorians Decoded’ exhibition has been conceived in order that viewers can explore our own relationship with technology and the impact telegraphy had on the world during the nineteenth century. The exhibition does this through the lens of the artistic imagination and well-known names such as Edwin Landseer, James Tissot and Edward John Poynter, as well as lesser known artists: James Clarke Hook, William Logsdail and William Lionel Wyllie. The curators, Professor Caroline Arscott, Professor Clare Pettitt, and Vicky Carroll have clearly posed questions like: how did telegraphy contribute to the Victorians understanding of their place in time, how did changing perceptions of distance alter social expectations and artistic imaginations, and how did the Victorians respond to coding and decoding?

Arscott’s own research has become increasingly scientific over the last few years, and her hand can be felt in much of the display, although one should not underestimate the involvement of the wider community of researchers and curators, e.g. Cassie Newland (who has been working on the ongoing project Scrambled Messages) and the Guildhall Curator, Katty Pearce.

There is a weighted scientific side to this exhibition, as personified in the display of personal notes and papers of telegraph pioneer Sir Charles Wheatstone, as well as examples of his first machines, code books, communication devices, and samples of the transatlantic telegraph cables. There is also a wonderful example of a wooden telegraph machine made by Wheatstone, which mirrors the fretwork of the wooden accordion placed next to it in the cabinet. Whilst this seems typical of Victorian indulgence, as soon as one discovers Wheatstone was an accordion maker by trade, the detailing soon becomes categorised as a practical and sound decision.

The fretwork matches that of the accordion and, in an inspired move, it also matches ‘The Great Grammatizor’ which is a specially-designed messaging machine allowing the public to create a coded message of their very own. ‘The Great Grammatizor’ will no doubt be a hit with children (and adults) visiting this exhibition and I fear the fruit-machine-like handle may be subjected to some months of overwork.

In order to create a narrative about telegraphy the exhibition has been arranged into four themed rooms: Distance, Resistance, Transmission and Coding.

Distance

The ‘Distance’ room helps illustrates the monumental achievements the Victorians had in laying cables across the Atlantic Ocean floor, from Valentina Island in Ireland to a tiny fishing village called Heart’s Content in Newfoundland, Canada. The cables were a ‘girdle around the earth’ whose technology would bring ‘all the nations of the globe within speaking distance of each other’. The Victorians were optimistic. The cables weighed more than one imperial ton per kilometre and it took nine years, four attempts and the world’s (then) largest ship, Brunel’s SS Great Eastern, to complete this political and imperially energising job. The scale of insight, invention and commitment to this accomplishment was phenomenal and it revolutionised the world. The room’s display of battery cells and the like seeks to underline this revolution, e.g. the Battery of Daniell Cells (1840 – 1860, King’s College Archives, London).

The cables, a small section of which are on display in this room, enabled same-day messaging across the continents for the very first time and with that, they introduced new business and marketing opportunities into both sides of the Atlantic. It is fair to say, the telegraph introduced the suggestion of the twenty-first century, of a world which relies upon international markets and communications. Speed was and still is the key for maintaining these relationships and enables one to quickly recognise why the Military and Government were the first to embrace telegraphy. It took approximately one minute for eight words to be transmitted. These technological innovations offered artists new insights and opportunities for representing conversations being had in a never before seen manner, in a new visual way.

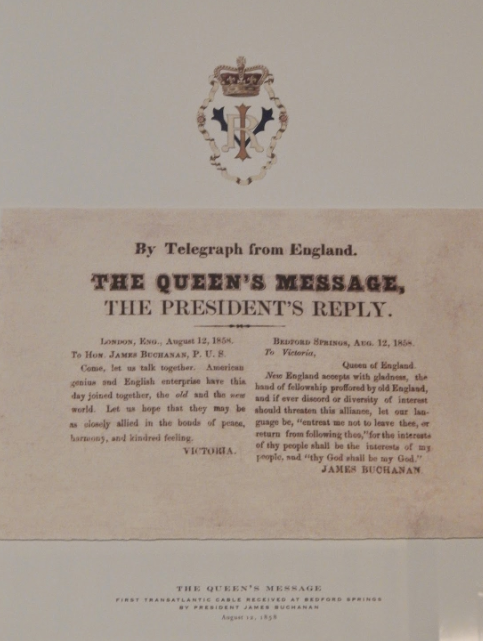

Royalty endorsed this exciting new world of communication, and the first ‘official’ transatlantic telegraph was sent by Queen Victoria to the American President, James Buchanan, on 16th August, 1858.

In this room there are numerous beautiful paintings, not least being William Ayerst Ingram’s Evening (1898, Guildhall), This Whisterlesque piece is testament to several themes in the room, the sense of space, time and distance being the most obvious. Ingram’s soup like sea is untouchable and insurmountable, it dwarves the small boat on the horizon which our eye has to seek to find. No doubt the boat would be extremely sizeable if nearer, and yet it disappears before our eyes, almost turning into a wisp of a cloud as it is carried far, far away from the terra very firma our feet inhabit.

But the knowing viewer of this work, is content because he knows man’s ability to rule the seas, to overcome the impossible, to be both here and there. The tiny boat on this vast seascape signifies man’s ability to defy the natural world, to defy the natural order of things. The light within this work cannot be comprehended until stood before it.

Another painting brings the reality, the noise and fuss of the busy seas to our attention: William Lionel Wyllie’s Commerce and Sea Power (1898, Guildhall). The rolling brown sea does not offer a poetic insight into man’s visionary technologies as Ingram does, instead we are greeted by the noise and bustle, we are looking at the smell and sound of commerce and international markets which Wyllie has been transported for us onto the windy seas. This work feels more of an observation than a judgement or vision, it is a type of reportage, permitting us to glimpse into the busy world of a once unchartered water.

Resistance

Man’s relationship to the natural world has and always will remain integral to the way we view the world around us, whether it be in a Romantic ‘Wanderer above the Clouds’ manner or the brutal image by Landseer, Man Proposes, God Disposes (1864, Royal Holloway). Landseer’s work never ceases to impress and it is a delight the Guildhall saw fit to include it in the ‘Resistance’ room. This room seeks to show a world that still had to overcome difficulties: technology could be conquered but could the natural world?

Man Proposes, God Disposes is a translation of the Latin phrase Homo proponit, sed Deus disponit from Book I, Chapter 19, of The Imitation of Christ by the German cleric Thomas à Kempis. Whilst the painting probably does little to abate unfounded fears about the predatory nature of Polar bears, it is in itself a wonderful piece of imaginative fiction, inspired by the search for Sir John Franklin’s lost 1845 expedition which disappeared in the Arctic. Ironically, Franklin’s lost ‘ghost ship’ has just been discovered in the days to the exhibition opening.

The scene depicts the scattered wreckage of Franklin’s expedition: one can identify a telescope, a mast with the tattered remains of a red ensign and a sail hanging from it, two polar bears, and human bones. The polar bears aggressively gnawing and gnashing their teeth among the ensign and the bones, and we as viewers are terrifyingly reminded of our fate should we endeavour to endeavour. Man is always destined to be defeated, to be overcome by the natural order of God’s grand design. Civilisation and imperialism has been defeated by ‘nature, red in tooth and claw’ and the bones are pure pathos. William Michael Rossetti described the bones as ‘the saddest of membra disjecta’ (scattered remains). Landseer’s post-Romantic sublimity is extremely powerful, and recalls Caspar Friedrich’s Das Eismeer (1823, Hamburg).

Reception of the work was generally positive, The Art Journal described its ‘poetry, pathos, and terror’ and recognised its ‘tragic grandeur’, and the Saturday Review praised its ‘sublimity of sentiment’. It is right that Victorians Decoded asks us to consider our place in the world, just as the Victorians did during this period of innovation, and remind us too that we are but temporal beings, with both limited power and time.

When the painting was exhibited at the 1864 Royal Academy summer exhibition, Lady Franklin refused to attend to the painting, calling it ‘offensive’. No doubt thinking of one’s husband dying at the other ends of the world was too much, but as a metaphor and cautionary warning, Landseer’s piece is a marvel. It is important we resist it though, and we should remind ourselves it is a fiction, but it also provokes us to consider the consequences of man’s place within the world, and the inevitable failure of man’s technological innovations: Man’s resistance belies God’s resistance (to man’s advances) (in the context of the Victorian mode of thinking about the world).

Damage to vessels during the Atlantic cabling project hindered completion and transmission, and there were also other issues for the resistance in the 2,754 km of copper cables was so new that engineers barely understood it, making the passing of signals very difficult. Although the Queen’s telegraph had been successful, the cables needed to be repaired within a few weeks and technological teething problems were part of the process (one we recognise more generally in our world of regular software updates and releases).

Two never-before-seen paintings will be on display, Thomas Hope McLachan, The Isles of the Sea (1894, Guildhall) which evokes a similar sublime feel to Landseers work, only without the humanity and pathos, and Peter Graham, Ribbed and Paled by Rocks Unscalable and Roaring Waters (1885, Guildhall).

The Isles of the Sea has been in conservation for the last year and despite the nicotine yellow varnish looking images on the internet, the colour of the painting is decidedly more subtle. The work is also more detailed and in the bottom left there are three birds battling the strong winds as they attempt to leave the canvas. The work is thick with impasto and the light is surprisingly effective. The conservation and cleaning has certainly paid off and the painting really offers a Turneresque sublimity to the room.

A particularly exciting work is Frank William Warwick Topham’s Rescued from the Plague 1665 (Guildhall) which presents a naked being delivered from a building to a man and young woman (possibly child) in order to escape the plague. The child is deliberately naked to escape the death which hangs about those within her own household (more likely his really). A young woman stands below with new clothes ready to cloak this young Christ’s body. The Christian message is confusing here, the Mary Magdalene and Mother Mary figures are both dead and alive, the roles and certainties of these messages are unclear. One woman slumps against the doorway which has a red cross daubed across it, whilst the other stands penitent ready to clothe and protect the young ‘Christ’ descending the cross. The infection, as a form of ‘message’, is denied by the removal of the naked ‘Christ’. Instead the message of rebirth, of a life affirming Christianity comes through strongly, and so with bodily health being preserved, the child’s life may continue. The (Christian) message lives on. This work is a interesting way of examining ‘transmission’ messages and yet the label information is reluctant to celebrate or is perhaps deaf to the Christian message of this work in any depth: I fear this is curatorial practice more generally (we must keep the labels secular, accessible, open etc.). We should also ask ourselves how flexible or tenuous the theme of the exhibition is, however exciting the paintings are.

Transmission

Customers desired speedy telegrams as did businesses, and telegraph companies sought to expedite communication although lines needed to clear between signals. In order to speed things up smaller signals were sent although this required ever more sensitive detectors and illustrates the increasing refinement of the technology. ‘Thousands of miles of cable laid beneath the ocean sped up communication in a way that few people – not least, artists – could have ever imagined, forcing them to re-evaluate distance and time. There is no doubt that telegraphy transformed people’s lives’ writes Carroll.

The paintings in this section of the exhibition explore the progressive ways of transmitting messages old and new, and asks the viewer to consider the clarity of messages. Images such as James Clarke Hook’s Word from the Missing (1877) and William Logsdail, The Ninth of November, 1888 (1890) lend themselves to understanding the various means of indirect transmission, whether that be via generations or through political distance, or even light, and whether the messages are thwarted or enhanced through close contact or enforced physical separation.

The lovely Word from the Missing shows a woman and two children on the beach. The woman holds a large square wicker basket with one hand, and she bends down picking up bits of driftwood with the other hand. The rose colour of the woman’s top is highlighted by the darkness of her hair and the basket.

The two children are blonde and they stand barefoot in the shallow ebb and flow of the sea. The young boy, we presume her son, holds aloft a glass bottle with a message inside it, for the little girl to see. She bends with her hands on her knees as she looks intently at the piece of paper inside. The naivety and innocence of the children is charming, as is their excitement at the discovery of this seaweed covered treasure. Is this family awaiting a message? We can perhaps read that the family await news for the head of the household to return from the sea, just like the bottle, but news of him seems never likely to come. Does the woman wait patiently hoping the sea will spit out her husband just as it did the bottle in some Conradian way? It is a bitter message for us, the viewer, to ponder. This message-in-a-bottle form of communication is a world now past: the children’s world of innocent timeless pleasures is as liable to be smashed as the glass bottle is against the rocks in the background, as perhaps their father was. This hopeful indeterminate message-in-a-bottle symbolises a world superseded by the high-tech advances of telegraphy. But for this family, there is no ‘word from the missing’, there is no personal message, and there will be no telegram.

The correlation between news, personal or otherwise, and speed is an important message within this exhibition. Modern communications could offer solace but they could also offer protection: one of the first indications the new telegraphy technology would offer social assistance was evidenced by a telegraph which reported a murder. One John Tawell was arrested and subsequently hanged due to a telegraph which identified which train he had got on after his heinous crime. It would have been interesting for something like this to be included in the exhibition as well, after all, the curators seem keen to make visitors think about social issues.

The other painting of note in this section is The Ninth of November, 1888 which is a staggering piece of realism. It shows the Procession of Sir James Whitehead, Lord Mayor 1888-1889, passing the Royal Exchange which was has been destroyed by fire twice. The present building was designed by William Tite in the 1840s and was home to the Lloyd’s insurance market for nearly 150 years.

Logsdail’s painting is a busy, large image showing the arterial cable of the Lord Mayor’s parade. But this message is a weak one, being run on a small budget with only three footman, and thin scrawny ones at that. The parade is known as being the shortest one ever, and so, this cable of communication was cut short. The recipients are busy stealing, chatting and ignoring the formal message: look at the child on the left, stealing some fruit, or the one on the right, pinching the hat. This traditional scene of pomp and circumstance has been redirected into a sorry crackling message. It really has rained upon this parade.

One message that is not brought out in this example, is one of inheritance. I ask you to compare Frank Cadogan Cowper’s An aristocrat answering to the summons to execution, Paris, 1792 (1904). The uniform and the off-centre aslant pose and costume is surely reminiscent? Let us not forget that artistic messages often outlive their own contemporary attempts at communicating things of note.

Coding

In this final section of the exhibition, coding is tackled. Having established the technology sufficiently to create and transmit clear messages, secrets were denied and anybody could read the communications being sent: privacy then became an issue for the Victorians. Gradually and yet inevitably, people began to develop their own methods of coding their messages and in this room transatlantic code books are on display alongside paintings that reflect the concept of coding within human interaction.

In order to shorten personal messages and hide content from the handling telegraph clerks, people resorted to code books and ciphers. Police code books and private codes are included in display cabinets, such as the Police code ‘FELONY FENCEFUL FETLOCK’ which translates as ‘the suspect has two teeth, out in front, a slightly turned up nose and is a smooth talker’. Presumably this was a regularly transmitted message, worthy of a code.

As part of this section, the Great Grammatizer is featured. As already mentioned, this machine allows each visitor to scramble and code their own messages, and may even turn them into eccentric poems. This bizarre steampunk machine is the result of a competition won by Alexandra Bridarolli and was inspired by ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’ a story by Roald Dahl from his collection Someone Like You (1953). It is a delightful albeit smaller than expected addition to the exhibition.

In this final section you will find James Tissot, The Last Evening (1873, Guildhall) and Solomon Joseph Solomon, A Conversation Piece (1884, Leighton House Museum) side by side. The Guildhall describes Tissot’s scene as ambiguous, saying it is a scene which takes place the night before the boat sets sail. The relationship between the characters is unclear, one man leans practically over a young female, who gentle rocks backwards on a wicker chair. The man wears a wedding ring whilst the woman does not. Two men look on, perhaps one is her father, and they seem to be discussing this potential union. Are we to assume the match is, in the first instance, considered possible? Have these two men misunderstood the young man’s intentions, or do they know it only too well? Perhaps the girl misunderstands the young man? None of the characters seem to be engaging fully with each other and their communication is without eye contact, the messages are becoming depersonalised in this painting. The ‘new’ form of communications are disconnected and each individual is at risk of remaining just that, individual, separated from meaning. After all, the wires of communication are so busy and liable to confusion and misdirection, and Tissot makes sure we understand this by replicating the many variants of meaning, telegraphic or otherwise, in the messy tangled ships masts in the background. The heavy patterned fabrics also seem to reiterate this knotted message.

Perhaps this interpretation is too negative though, and the work is suggesting that due to the rise of the telegraph a young woman’s future could offer her greater opportunities? Are we to consider that the very young girl on the left hand side of the painting, the one who both surveys the scene whilst listening to the two older gentleman, may perhaps have a different future from one which results in a woman being saddled with a man who may accost other women when out of sight? It seems the painting does encourage one to ask about space and people’s relation to space. The young man has yet to learn that only he is an ocean apart from his wife, that he remains connected to both worlds in a way that has yet to become apparent to him. The painting also asks one to ponder the future, and if we return to Landseer for a moment, do we see man as continuing to propose – to propose to go against the natural order?

Solomon’s A Conversation Piece is perhaps also in this vein: each person looking away rather than making direct eye contact with the other characters within the scene. The detail in this work is worthy of Tissot himself, and recalls his Hide and Seek (1877, NGA). The luscious interior is delightfully Victorian and permits the viewer a moment of well-earned reverie at the end of this thought provoking exhibition.

A well-known and visitor attracting piece is Leighton’s Music Lesson (1877, Guildhall). Music Lesson is a beautiful work which will no doubt please visitors but does the theme of ‘Coding’ become a little diluted at this point in the exhibition: how far is the metaphor being stretched? Is the inclusion of the work for the team’s benefit, for the visitors or for general celebratory consumption? After all, visitors will inevitably be expecting some big names in an exhibition which mentions the ‘Victorians’. Leighton suitably and quietly obliges, despite being consistently written out of any modern historicisation of the nineteenth century – Leighton, for all his glory and panache, is never ‘edgy’. It is evident why Arscott has included this work (and I believe it is Arscott’s choosing as she writes about this work elsewhere): Leighton ‘transmits’ information in this painting, he transmits knowledge, sound and aesthetics. It is a sublime piece of synaesthesia but it feels a little awkward here, a little too easy a choice.

One piece within this room that seems to stretch the exhibition too far is De Morgan’s Moonbeams Dipping into the Sea (1900, De Morgan Foundation). The painting is exceptional and a delight to discover in the exhibition, but one can’t help wondering how far the curatorial mind wandered. Yes, De Morgan did have apprehensions and beliefs about sequential spirit messages being received on earth via light sources, but Arscott’s interpretation that light may also ‘additionally stand for the transmission of spirit messages’ seems, whilst apt in other contexts, to have asked too much of a visitor that has just been looking at code books and battery cells. I suspect most visitors will appreciate the beautiful reprieve when enjoying this work, but I am not convinced many of them will buy its intrusion upon an exhibition that is for the most part exceptionally well considered.

The Guildhall certainly houses a fine display and at no cost one can leisurely re-visit and decode the Victorian mind as often as one likes over the next couple of months: I will certainly be doing this. This exhibition is, as Arscott puts it, evidence of ‘Art itself….[being] transformed as telegraphic systems were established’ and as one wanders through the exhibition space, you will find yourself gentle prompted into thinking about the nineteenth century, whether that is through examination of Victorian interiors, seascapes, or shipwrecks. The questions or connections asked of visitors are sometimes a bit over-stretched, but I suspect that is unsurprising of a team that meet once a fortnight to discuss their ideas about the same subject. Nonetheless, I can’t think of a more worthy way to spend my time. This exhibition is free. FREE. The Guildhall’s message about accessibility is NOT to be missed. Compare this free exhibition with any of the other major London galleries exhibitions on at present and ask what message those places are presenting about the arts. Ask yourself what those places think of your place as a visitor and as an educated commentator upon public collections. Then ask yourself about the purpose of this exhibition and you will see how it tries to emblematise democracy from start to finish, from the moment you walk in until the moment you grammatize. If you leave this exhibition with music in your ears and moonbeams in your eyes, then the messages sent have certainly been clearly transmitted.

Special curator talks about the exhibition will take place on 29th September 2016, 27th October 2016, 24th November 2016, 15th December 2016 and 19th January 2017.

There is a wider programme of research being undertaken which commemorates 150 years and further information on events can be found on Scrambled Messages. To coincide with the exhibition, Scrambled Messages is running a photography competition for GCSE and A-level students.

Leave a comment